Dopex: Options, SSOVs, and Atlantic Options

Navigating DeFi Ep. 2

What’s up everyone. Welcome to Navigating DeFi — a podcast where we cover DeFi projects and concepts in depth. This week we’ll discussing a project called Dopex and by the end of the episode you’ll know how options trading works, how options are priced, why one might want to use options, and how Dopex makes options accessible for all types of users.

Reminder: These are show notes, thus they are a combination of written and borrowed content constructed to tell a coherent story. I try my best to cite all sources appropriately.

This week’s episode can be found here:

Intro

Dopex is a decentralized options protocol built on Arbitrum, which is an Ethereum layer 2 solution. Dopex was designed to maximize option liquidity, minimize losses for option writers, and maximize gains for option buyers — all in passive manner for liquidity contributing participants.

Background on Options

Let’s start by providing a background on options, since they’re the key to understanding how Dopex works. Options are financial instruments that give buyers the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at an agreed-upon price and date. There are two types of options: call options and put options.

A call option is a contract that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation to buy an asset. To be more specific, a call option gives its owner the right to buy an underlying asset at a given strike price on a certain date, know as the expiry date. The strike price is just some value that is agreed upon when the options contract is first written.

A put option is the exact opposite of a call option. It’s a contract that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation to sell an asset at the strike price.

Users will buy call options when they are expecting the price of an asset to go up, and will buy put options when they expect the price of an asset to go down.

Here’s an example of how options work:

Let’s say that it’s January 1st and the price of one ETH is $1,000, but I think that by the end of the month that the price of ETH will be $2,000. I could buy 10 call options at a strike price of $1,000 for a .025 ETH premium per contract which would expire on January 31st. So the total cost for these call options would be 0.025 * 1,000 * 10 = $250. Each contract then gives me the right to purchase 0.1 of an ETH at the price of $1,000 per coin. This means I can buy one ETH at $1,000 when the contract expires at the end of January: (10 x 0.1=1).

From here there are two scenarios:

When the contract expires, ETH’s price is $2,000. I exercise my call option and make a $1,000 profit (2,000 - 1,000 = 1,000). Minus my premium, I walk away with $750 in gains.

When the contract expires, ETH’s price is $500. I can decide not to exercise my call option because it’s “out of the money.” In this scenario I would have lost $250, the price of the 10 contracts.

Through this example we can see that buying options allows users to limit their risk while still having large profit potential. The only risk you take on is the premium you paid for the options.

That said, options trading consists of two sides of the market: options buyers and options sellers. Option buyers are the users we just discussed. Options sellers create call and put options contracts that are listed on an options exchange. There are a few reasons one might decide to be an options seller:

You want to collect the premium for the option

Time decay works in your favor, if there is no price movement, you will make a profit

Among other things, but we won’t cover them here to save time.

So, to wrap this section up, we have call options (which are for people who want to capture the upside price action of an asset) and we have put options (which are for people who want to profit from the downside price action of an asset) — this category of users are called option buyers. And, as we just touched on, the other side of the market consists of options sellers who create the contracts presented to buyers. From here, options can turn into a pretty deep rabbit hole, but I’ll try to weave in some of the more complex topics as we dive into Dopex and how it works.

For now, Dopex has two products that users can interact with: liquidity mining pools and Single Staking Option Vaults (SSOVs), but they also have products in the pipeline such as option pools and Atlantic options. We’ll touch on tokenomics and liquidity mining at the end, so let’s start with Single Staking Option Vaults and the rest of their pending products.

What are SSOVs?

Single Staking Option Vaults, or SSOVs, allow users to lock up tokens for a specified period of time and earn yield on their staked assets. When users deposit an asset to an SSOV contract, the contract then sells a user’s deposit as call options to buyers at fixed strike prices that the user selects for a set expiration date at the end of the month.

SSOV call options are either at the money, out of the money, or far out of the money. For a call option, at the money means the strike price is equal to the current market price. Out of the money (OTM) means the strike price is higher than the current market price of the underlying asset. And these are just labels for identifying the success, or lack of success, of a position.

SSOV Depositors

Here’s how SSOVs work for SSOV depositors (i.e. options sellers):

At the beginning of the month, strike prices are set for the month-end.

Users then lock assets into a vault and select fixed strikes that they’d like to sell calls at.

The contract then deposits the users' tokens into a single staking pool to earn farming rewards and to earn yield from selling what are known as “covered calls.”

Covered Calls

A covered call is an options strategy used to generate income in the form of options premiums. To execute a covered call, a user holding a long position in an asset then writes (sells) call options on that same asset.

But, as always, let’s explore this with an example:

Let’s say a $100 call is written on an asset trading at $10, and the writer receives a premium of $1.00, the maximum potential profit is the $1.00 premium plus a $10 appreciation of the asset.

The maximum loss, on the other hand, is equivalent to the purchase price of the underlying asset minus the premium received. This is because the asset could potentially drop to zero, in which case all you would receive is the premium for the options sold.

The maximum profit of a covered call is equivalent to the premium received for the options sold, plus the potential upside in the asset between the current asset price and the strike price.

A covered call really serves as a short-term hedge on a long position and allows investors to earn income via the premiums received for writing options. However, a covered call forfeits gains if the price moves above the option's strike price since the user is obligated to provide shares of an asset if option buyers exercise their calls.

The highest payoff from a covered call occurs if the asset price rises to the strike price of the call that has been sold and is no higher. This is because the investor benefits from an increase in the asset’s price and collects the full premium of the option as it expires worthless. Remember: if the asset doesn’t hit the strike price of the contract, the buyer won’t exercise the call option, so this causes the option to expire “worthless.” In the case of Dopex SSOVs, ATM (At The Money) options generate the most yield and far OTM (out of the money) options get the least yield.

SSOV depositors receive yield proportionally to how close to ATM strikes are being locked in. In the event that a set of contracts is OTM or far OTM, users won’t lose any value in US dollar terms, however, they do have a chance of losing a percentager of staked assets.

To be more specific: SSOV depositors users will not be at risk of losing any notional USD value by staking their assets. However, in the case that the token increases rapidly they will lose potential upside. In the case that call buyers are in net profit at the end of the month, depositors will lose their staked tokens but will make a profit in US dollar terms. Think of it as a taking profit at the strike price + premiums collected.

Options buyers

Now, for the other side of the SSOV market, the options buyers. Buyers can simply purchase calls from the vaults using the base asset. For example: if they want to buy a DPX call option, they go to the DPX vault, choose an available strike price, choose the amount of contracts they’d like to buy, and pay the premium to confirm their position. All options are auto-exercised on the expiration date by default and can be settled any time after expiration date.

As we discussed earlier in the episode, call options buyers are in the money if the price of the underlying asset is higher than the strike price. If the price of the underlying asset on the expiration date is at or below the strike price, the option is considered worthless and the buyer simply loses their premium. Pretty straightforward.

SSOV Summary

All-in-all, SSOVs as they’re currently designed, allow single sided depositors to sell covered calls on assets while allowing buyers to buy call options on those assets — presenting a unique yield earning opportunity for depositors and accessible liquidity for buyers. These strategies could be interesting for holders of a particular asset who are long term holders and are looking for a more reliable source of yield on that asset.

Option Pools

In this section we’ll option pools, however before we dive in I want to be clear that option pools are not live yet and are still in development, so some of the details in this section could be subject to change.

Option pools will allow users to earn passive yield by providing base asset and quote asset liquidity for users who'd like to buy call and put options. In this context, a base asset is the asset underlying a call option and a quote asset is the asset underlying a put option. But really all of this is just a complex way of saying that option pools allow anyone to earn yield passively by selling options to buyers with minimal interaction with the protocol.

To use option pools, users will simply deposit base or quote assets to a pool which would be utilized as liquidity for users looking to purchase call and put options. At the end of every week or month, pool participants would be able to collect their share of pool holdings including premiums paid for all options relative to the size of the pool as well as additional DPX token rewards at the initial stages as an incentive for providing liquidity.

So anytime someone buys an options contract from the pool, the premium they pay is distributed proportionally across the depositors in the options pool. Users will also receive additional DPX token rewards alongside the premiums.

In-case losses are incurred by the pool, which happens when purchasers make a net profit on their option purchases, pool participants will receive rebate tokens - called rDPX - which are minted equivalent to 30% of all losses incurred by the pool. This makes providing liquidity to Dopex a better alternative to options writing on other platforms because the users downside risk is minimized.

In short, option pools on Dopex allow users to easily become options sellers by simply providing liquidity for a given asset in return for yield in the form of premiums, the DPX token, and in some cases the rDPX token.

Volume pools

Living alongside option pools are what Dopex calls volume pools. Volume pools are created for the purpose of boosting volume within the protocol by offering a 5% discount on all option purchases made using volume pool funds.

If we revisit option pools for a second, we covered how users are heavily incentivized to provide liquidity, but incentivizing users to provide liquidity could make for a liquidity rich protocol without genuine usage. In other words, there could be tons of liquidity (i.e. option sellers), but no options buyers. This would lead to a chicken and egg problem in terms of generating actual usage of the protocol. To incentivize option market professionals to utilize the protocol and actually purchase options, Dopex will be introducing volume pools.

Volume pools allow users to deposit funds prior to a weekly epoch, or set period of time, and use funds from the pool to purchase options from any option pool at a 5% discount. Volume pools create an arbitrage opportunity for sophisticated option traders who can purchase options at a discount and immediately arbitrage them against other exchanges for a quick profit.

Volume pool depositors are also given DPX token rewards in the initial phases to further incentivize pool usage. At the end of every epoch, users can withdraw any excess funds from the volume pool, however they would have to pay a 1% penalty at withdrawal for non-usage of funds. All penalties are claimable by DPX governance token holders in the form of protocol fees.

Basically, the goal of volume pools is to get option buyers to pre-commit capital for purchasing options and incentivizing them handsomely to do so.

Dopex AMM

Underlying these pools is the Dopex AMM. If you’re unfamiliar with AMMs, they are automated market makers that price assets according to a specific price curve or formula. So any time a trade is made on a given pair in an AMM, it’s price is determined by the underlying formula. The Dopex AMM uses assets from the asset pools along with what’s called Black-Scholes pricing formula that accounts for volatility smiles to allow anyone to purchase options based on strikes of their choice for future expiries.

I know, that’s an absolute mouthful, but to understand the pricing formula used by the Dopex AMM, we also need a little bit of background on the Black-Scholes formula, volatility smiles, and volatility surfaces. I’ll give a bit of a financial trigger warning, because we are about to go down the rabbit hole.

Black-Scholes

The Black-Scholes formula is a mathematical model designed to give traders a theoretical price of options. I want to highlight here that the “price” of an option is the same exact thing as its “premium.” So in other words, the Black-Scholes formula is trying to calculate a theoretical premium for options.

The primary goal of option pricing is to calculate the probability that an option will be exercised at expiration and assign a dollar value to it. The greater the chances that the option will be profitable, the greater the value of the option, and vice-versa. If you’re someone selling options, you want to make sure that the cost of what you’re selling grows proportionally to the likelihood that it’ll be profitable to the buyer. And if you’re a buyer, you want to make sure you’re getting a fair deal on the option relative to its risk profile.

The Black-Scholes formula uses the volatility of an option as an input to price options. Option volatility measures how the price of the asset will move in the future. The greater the volatility, the more the asset moves. The reason we have to look at volatility when pricing options is due to the fact that higher volatility increases the odds that an option will end up profitable and even surpass the strike price by a significant amount.

However, the Black Scholes model assumes that the volatility of an option is constant but in reality, it is always changing. As a result of this, the market price of options with the same strike price and expiry date are prone to diverge from their theoretic price determined by the Black Scholes formula. This inconsistency forms what’s called a volatility surface.

A volatility surface is a three-dimensional plot of the implied volatility of an option. The term implied volatility refers to a metric that captures the market's view of the likelihood of changes in a given security's price. This is important because the rise and fall of implied volatility will determine how expensive or cheap time value is to the option, which can, in turn, affect the success of an options trade. Here time value refers to the portion of an option's premium that is attributable to the amount of time remaining until the expiration of the option contract. And it’s generally the case that the more time that remains until the option expires, the greater the time value of the option.

Going back to volatility surfaces: If we assume that the Black-Scholes model is correct, the implied volatility surface should be flat. In reality, this is almost never the case. The volatility surface is not flat and instead tends to vary over time due to the assumptions of the Black Scholes model being false at times.

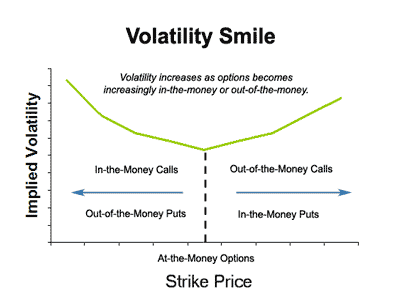

While this can be tricky to wrap your head around, all you really need to remember is that for any given strike price, implied volatility will likely be increasing or decreasing as contracts approach their expiration date, giving rise to a phenomenon known as a volatility smile.

What is a Volatility Smile?

A volatility smile is the shape of the graph that forms as a result of plotting the strike price and implied volatility of a group of options with the same underlying asset and expiration date, but different strike prices. When the implied volatility is plotted for each of the different strike prices, a U-shape resembling a smiling face forms, hence the term volatility smile.

What’s important to remember here is that the Black-Scholes model does not predict the volatility smile, which is a fancy way of saying that it doesn’t predict the increase in implied volatility of an option as it goes further in or out of the money. As mentioned before, the Black Scholes model predicts that when plotted against varying strike prices, the implied volatility curve is flat. The Black Scholes Model assumes that the implied volatility would be the same for options with the same expiry and underlying asset, even if the strike prices differ.

What’s important to remember is that volatility smiles are the result of increasing volatility among options as they go further in the money or further out of the money — and the Black Scholes formula doesn’t predict such behavior. So in order to accurately price options, one must take volatility smiles in to account.

Dopex AMM Pricing Formula

Now that we get the gist of the Black Scholes formula, volatility surfaces, and volatility smiles, let’s re-summarize what the Dopex AMM does. The Dopex AMM uses assets from the asset pools along with Black-Scholes pricing formula to allow anyone to purchase options based on strikes of their choice for future expiries.

The cost of options purchased are calculated on-chain based on the Black-Scholes formula — using implied volatility and asset prices retrieved via Chainlink adapters — and passed through a function to determine volatility smiles based on the realized volatility of the asset and past data, which ensures that users are presented with accurate option prices that reflect real risk and market behavior.

Why does Dopex need an AMM?

Before we move to the next product, I want to briefly touch on why Dopex needs an AMM in the first place. In traditional finance, market makers play a key role in options trading. They are essentially there to keep the financial markets running efficiently by ensuring a certain level of liquidity around various options markets. Without liquidity, no one can trade options. However, they are not your average trader; they are professionals that often have contractual relationships with the relevant exchanges and carry out a large volume of transactions and there is a certain level of expertise required to partake in market making activities.

Dopex effectively removes this barrier to entry, allowing anyone to become a market maker through option pools, which are powered by the underlying Dopex AMM. Since option pools are powered by the Dopex AMM, liquidity providers simply need to provide capital, and don’t have to worry about pricing options, maintaining a healthy market spread, so on and so forth. Not only that, but Dopex even goes out of their way to cover up to 30% of a pool’s potential losses with rDPX as mentioned before... not a bad deal!

Atlantic Options

Now let’s discuss Atlantic options, one of the newer innovations in the Dopex ecosystem. The goal of Atlantic options is to increase the capital efficiency of selling options contracts. As we highlighted before, when users want to sell options contracts, they must provide the underlying asset upfront as collateral.

If we circle back to SSOVs for a moment, remember that contract depositors must deposit an asset to an SSOV contract, which is then used to sell call options to buyers. This is known as “providing collateral” and leads to an obvious capital inefficiency because the deposited collateral isn’t doing anything from the time it’s deposited to the expiration date of the contract. That’s where Atlantic options come in.

Atlantic options will work like the options we’ve covered throughout this episode however the collateral underlying the options can be moved to take advantage of other opportunities in the DeFi ecosystem until the expiry date of the contract. As usual, let’s explore with an example. It’ll be kind of long, but bear with me:

Let’s say that User A has sold an Atlantic put option contract on ETH with a strike price of $3,000 to User B that is set to expire in one month. User A will have to back that option with $3,000 in cash collateral in the event that User B exercises their contract. If ETH trades below $3,000 one month from now, User B will exercise their contract and User A will have to buy User B’s ETH above market price. If ETH trades above $3,000, then the put option will expire worthless and User A will keep the premium paid by User B.

However, since this is example an Atlantic put option, User B can actually do something pretty cool as long as the option isn’t expired. User B can put up the underlying token — in this case ETH — to unlock usage of the collateral put up by User A. So in other words User B can provide some ETH to the contract, pay a small fee to User A, and borrow the cash provided by User A. With this cash they can go do whatever they want: buy some other token, yield farm, etc. as long as they return the cash before the contract’s expiry date.

If they don’t return the cash by the contract expiry, then the extra ETH put up by User B will be partially transferred to User A so all losses are covered. If nothing goes wrong and User B returns the cash before expiry, then User A ends up with the premium and the additional fee paid by User B to unlock the collateral — not a bad deal either way.

The fluid collateral provided by Atlantic options unlocks all kinds of use cases that are out of scope for this episode, but I highly recommend reading the paper on Atlantic Options to explore some of the new opportunities that will be available to users.

Tokenomics

Last, but not least, let’s talk about Dopex’s unique tokenomics model. Dopex makes use of two tokens within their protocol:

DPX — which is their governance token, incentive token, and fee accrual token

rDPX — which is their rebate token that can also be used elsewhere in the Dopex ecosystem.

DPX

DPX should be considered the primary token. It has a limited supply and as I just mentioned, is used for governance and accrues fees and revenue from pools and vaults.

DPX can be purchased on decentralized exchanges on Arbitrum, but can also be farmed by users who provide DPX / ETH liquidity Sushiswap on Arbitrum.

rDPX

rDPX is Dopex’s secondary token and is actually a more interesting experiment than DPX in my opinion. The rDPX token is minted and distributed for any losses incurred by pool participants. However, I should caveat that right now rDPX is minted through the same liquidity mining program as DPX in order to build up rDPX liquidity before option pools launch.

When the actual rDPX use cases are live, the amount of tokens minted will be determined based on the net value of losses incurred at the end of a pool's epoch. A percentage of the losses, which is determined by governance is minted for all pool participants after the epoch has ended.

rDPX doesn’t have a supply cap like DPX, but has mechanisms in place to keep it from being valueless while also providing intrinsic value to the token. For example:

rDPX could be a fee requirement for future app layer additions to Dopex such as vaults.

Dopex could support rDPX as collateral to borrow funds from Margin to leverage option positions.

rDPX could be usable as collateral to mint synthetic assets, commodities etc. which could further be used to create options for synthetic non-crypto assets.

Fee accrual can be boosted via staking rDPX.

... so on and so forth.

Liquidity Mining and Staking

As I just hinted at, both rDPX and DPX can be earned through their respective liquidity mining programs. Users can provide rDPX liquidity against ETH and provide DPX liquidity against ETH via Sushiswap on Abitrum, and stake that liquidity on Dopex to earn additional rewards.

If you don’t want to provide liquidity, you can also earn both rDPX and DPX through single sided staking. Users can simply purchase either token (or both) and stake them on Dopex to earn staking rewards.

Conclusion

So we just covered quite a few topics around options, option trading, option pricing, and how all of those mechanisms are re-imagined within the Dopex ecosystem. We also covered some specifics around Dopex including SSOVs, option pools, the Dopex AMM, Atlantic options, and their unique tokenomics model.

While I tried my best to thoroughly explain each topic, I’ve undoubtedly left out some specifics and nuances that I recommend listeners dig in to on their own. To aid in that journey, I’ve made sure to provide the resources I used to construct this episode.

If you enjoyed these notes, feel free to subscribe on Substack and YouTube to keep up with future episodes and I’ll see you all next week.